February 11, 2007

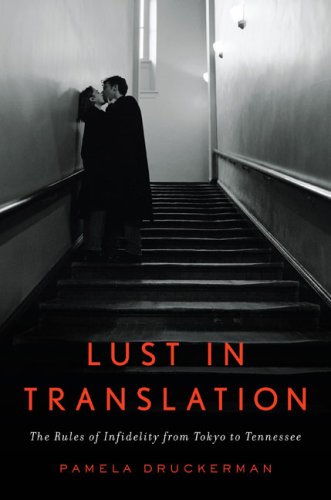

Lust in Translation

I would've assumed that Pamela Druckerman's new book, Lust in Translation, was great fun to write. But she says that's not wholly true. The book itself looks at how different cultures around the world deal with infidelity—how they view it, how they handle it, how it's accepted. So Druckerman, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, tracked down adulterers in Russia and South Africa, France and Japan, and asked them questions. She got loads of material, and the book is fascinating. But apparently, after months of nonstop chatting with people who were having affairs, it became hard for her not to be suspicious if ever her husband came back an hour late from "soccer practice" or didn't answer his cell phone. It's like the journalistic equivalent of medical students' disease!

I would've assumed that Pamela Druckerman's new book, Lust in Translation, was great fun to write. But she says that's not wholly true. The book itself looks at how different cultures around the world deal with infidelity—how they view it, how they handle it, how it's accepted. So Druckerman, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, tracked down adulterers in Russia and South Africa, France and Japan, and asked them questions. She got loads of material, and the book is fascinating. But apparently, after months of nonstop chatting with people who were having affairs, it became hard for her not to be suspicious if ever her husband came back an hour late from "soccer practice" or didn't answer his cell phone. It's like the journalistic equivalent of medical students' disease!Well, yikes. But like I said, it's a wonderful book. (Among other things, she investigates how the Japanese deal with the fact that one-third of all marriages are sexless.) One thing that stuck out, though, is that it seems that Americans—at least white, middle-class Americans—are the only people who, by and large, see an affair as a symptom of larger problems in a relationship. Bob must've cheated on Sue because they weren't getting along. Or whatever. It can't just be that Bob was attracted to someone else, or was bored and wanted a fling. No. There must be some deeper issue at work.

Russian people, to take just one example, don't seem to view affairs this way—people often have affairs simply because they have tiny apartments and share a bedroom with the kids, so adultery is the only way to have sex. And the fact that Russia has an absurdly high female-to-male ratio—because so many men die young—means that men are in very high demand, which creates additional pressure for infidelity. One 40-year-old women tells Druckerman that "if she didn't go out with married men she'd have almost no one to date."

Anyway, I hadn't realized it, but in the United States, an entire industry has sprouted up to help couples deal with the post-traumatic stress of an affair. And since Americans tend to think that infidelity is a symptom of some deeper problem, there's almost always stress. And, of course, the real problem is never the sex. It's the lying:

Since lying is the problem, truth-telling has become America's cure for infidelity. Many therapists believe that a wife is entitled to ask her husband for the details of every text message and encounter. The rationale is that the relationship between a husband and wife should be transparent. Some couples create a detailed chronology covering the entire period of the infidelity, even if it lasted for several years.Wow. Religious groups have also jumped on this idea that affairs corrupt a relationship, which in turn needs to be "healed." Many Christian organizations are big on truth-telling as therapy, along with religious counseling. (Interestingly, even though adultery is a sin, many Christian groups like the Covenant Keepers see it as a forgivable one, since divorce is so much worse.)

The process stops when the wife can't take it anymore, or when she's satisfied that she's overturned every lie she's ever been told. If any stray lies trickle out after this, the wife can have traumatizing flashbacks. There's no empirical evidence about whether this does any good.

People in some other countries didn't believe me when I told them about America's confession cure. They assumed that knowing the details of what happened would make someone feel worse. But the truth-telling cure has become so widespread in the U.S. that it's now gospel on websites for people with cheating spouses. On the frenetically active SurvivingInfidelity.com, "Erica" says she spent months interrogating her husband about her affair, and then "with the aid of my master calender, the 1000+ email, the photo albums, visa receipts, and his old expense reports, he and I set out to put all of those 2 1/2 years of infidelity on a timeline."

Now, obviously, anecdotal reporting isn't the same thing as doing extensive surveys and the like, but it was interesting that the people in France whom Druckerman interviews were mostly dumbfounded by the notion that couples should never have any secrets between them. That largely seems to be an American idea. (French people also don't appear to think that an affair is always a symptom of some horrific flaw in a relationship.) But then, looking at the statistics, French couples aren't any more prone to infidelity than American couples. It's just dealt with differently.