February 28, 2007

Fun With Monetary Policy

Jared Bernstein goes before Congress and points out that real median wages have stagnated since 2000, even though productivity has been rising. A wee problem, you might say. Bernstein blames the Federal Reserve, for trying to stabilize unemployment at a "natural" rate that is—in his view—much too high. And so long as there's slack in the labor market, there's no upward pressure on wages at the lower end. Hence the current situation. Anyway, here's the Fed's logic for acting this way:

In brief, and simplifying considerably, the original NAIRU story was based on the idea that the unemployment rate is usually at equilibrium, i.e., just where it should be in terms of supply, demand, and stable prices. Those unemployed at this "natural rate" can’t find work at the wage they think they deserve, but that’s because they have an upwardly skewed view of their worth (or marginal product). However, the monetary or fiscal policy authorities want to lower the unemployment rate, and get these folks a job, so they undertake stimulative actions (lower interest rates, tax cuts, etc.).So, to avoid an inflationary disaster—which would, horrors, be terrible for wealthy lenders—the Fed tries to keep things at the "natural level" by tinkering with interest rates. But Bernstein points out that the Fed's tale doesn't quite fit modern-day reality. Workers these days have considerably less bargaining power than their ancestors in, say, the 1960s—not least because union density has plummeted—so they can't push for ever higher wages every time prices go up slightly anymore. And that makes the whole "wage/price spiral" nightmare scenario less likely in this day and age.

Wage offers do rise, and these formerly jobless workers leave the sidelines and join the job market. However, firms offset their now higher labor costs by raising prices. Soon, the new workers recognize that they’ve been tricked: their reservation wage, though finally met, is not going as far as they think it should. They then demand yet higher wages and the wage/price spiral is underway. The only way to stop it is for unemployment to return to the natural rate, but by then, the inflationary damage is done.

Now that means, if I'm understanding correctly, that the current models are off a bit, the Fed could step on the gas somewhat harder than it's currently doing and reduce the unemployment rate even further without bringing about Armageddon. Median wages would rise for a change—and workers could finally share in all this marvelous productivity growth—but you wouldn't see some horrible inflationary spiral that destroys the country (or whatever it's supposed to do). Makes sense to me, I suppose.

Bad Teeth

The Washington Post has a horrifying story today about a 12-year-old kid who died of a toothache. The family had lost its Medicaid coverage and couldn't afford a routine tooth extraction, and so bacteria from the abscess spread to the kid's brain and he died--that is, after six weeks of hospital care and two operations that cost the state over $250,000. It's an extreme case, but it underscores the fact that the lack of dental coverage for low-income families is a much more serious problem than often thought. Malcolm Gladwell went over this in gruesome detail in The New Yorker a few years ago:

Several years ago, two Harvard researchers, Susan Starr Sered and Rushika Fernandopulle, set out to interview people without health-care coverage.... They talked to as many kinds of people as they could find, collecting stories of untreated depression and struggling single mothers and chronically injured laborers—and the most common complaint they heard was about teeth. Gina, a hairdresser in Idaho, whose husband worked as a freight manager at a chain store, had "a peculiar mannerism of keeping her mouth closed even when speaking." It turned out that she hadn't been able to afford dental care for three years, and one of her front teeth was rotting. Daniel, a construction worker, pulled out his bad teeth with pliers. Then, there was Loretta, who worked nights at a university research center in Mississippi, and was missing most of her teeth. "They'll break off after a while, and then you just grab a hold of them, and they work their way out," she explained to Sered and Fernandopulle. "It hurts so bad, because the tooth aches. Then it's a relief just to get it out of there. The hole closes up itself anyway. So it's so much better."Medicaid dental coverage seems to be a mess in most states--see this recent dispatch from Georgia, or this article from The Seattle Times. In many cases, recipients have dental coverage under Medicaid, but the reimbursement rates are so low that very few dentists will accept them. Legislatures rarely pay much attention. And then, of course, there's that whole slew of low-income folks who aren't even covered by Medicaid...

People without health insurance have bad teeth because, if you're paying for everything out of your own pocket, going to the dentist for a checkup seems like a luxury. It isn't, of course. The loss of teeth makes eating fresh fruits and vegetables difficult, and a diet heavy in soft, processed foods exacerbates more serious health problems, like diabetes. The pain of tooth decay leads many people to use alcohol as a salve. And those struggling to get ahead in the job market quickly find that the unsightliness of bad teeth, and the self-consciousness that results, can become a major barrier. If your teeth are bad, you're not going to get a job as a receptionist, say, or a cashier. You're going to be put in the back somewhere, far from the public eye. What Loretta, Gina, and Daniel understand, the two authors tell us, is that bad teeth have come to be seen as a marker of "poor parenting, low educational achievement and slow or faulty intellectual development." They are an outward marker of caste. "Almost every time we asked interviewees what their first priority would be if the president established universal health coverage tomorrow," Sered and Fernandopulle write, "the immediate answer was 'my teeth.' "

February 26, 2007

Don't Think of an Elephant

Here's a random historical tidbit: I've read the story about how Pompey, after his battlefield victories in Africa in 80 BC, asked the Roman dictator Sulla for permission to have a victory procession through the streets of Rome. Sulla relented, and Pompey decided to have his chariot pulled by elephants rather than the usual horses. Sadly, though, the elephants got stuck when they tried to wedge through one of the gates during the march, so Pompey had to unhitch them and wait for horses to show up. Bad luck, eh?

Now as I've always heard it, the story works as an allegory about how this ambitious young punk of a general was getting ahead of himself. That's how some of his contemporaries described the affair. But now Mary Beard, in a New York Review of Books essay, says that some historians think it was a sophisticated PR exercise. "The whole scene was, they have suggested, carefully stage-managed to demonstrate to the assembled spectators that Pompey had literally outgrown the traditional constraints imposed by the city and the norms of Roman political life." Now that would be clever. But would an audience really pick up on the message here? It seems like they'd just laugh at the stuck elephants and think the guy a buffoon. But maybe Romans were better at picking up on subtle hints. Dunno.

Who Controls the Nukes?

Most policymakers and pundits don't seem to know how to deal with Pakistan. (I certainly don't.) On the one hand, the United States wants Musharraf to be more aggressive about hunting down Al Qaeda operatives in North Waziristan. On the other hand, moving too aggressively against that part of the country might cause Musharraf's government to collapse, in which case radical Islamists could seize power--and with it, control of Pakistan's nuclear arsenal. Scary stuff.

At any rate, I'm curious to know what sort of safeguards Pakistan has in place to prevent its nukes from falling in the wrong hands, should, say, Taliban sympathizers in the intelligence services stage a coup (or whatever). The reporting on this front appears patchy. In 2004, Graham Allison warned that the security measures were still much too flimsy, and wanted the United States and China to do a thorough review of Pakistan's nuclear stockpile, in order to help Musharraf set up proper controls. That would involve a lot of delicate diplomacy--especially since Pakistan is understandably reluctant to open its arsenal up to outside inspection--but it doesn't seem completely undoable.

So what's actually being done? A Congressional Research Service report in 2005 noted that the United States was offering some assistance, but mostly to "focus on helping secure nuclear materials and providing employment for personnel, rather than on security of nuclear weapons." See also here. And last August, Pakistan declared that it had set up a "tri-command nuclear force," but it's not clear whether that would safeguard the weapons in the event of a coup. (In any case, the country's past assurances on this score have been fairly suspect.) Those seem to be the main media stories of late. Who knows, perhaps the administration really is doing all it can here, but I'd sort of like to see a closer investigation.

February 23, 2007

In Defense of Kucinich (Sort Of)

Daily Kos comes out swinging against Dennis Kucinich. I have to say, a few of Kos' complaints strike me as unfair--sure, the dude has a lot of wacky spiritual beliefs, but from a non-believer's perspective, all religious beliefs seem a little bizarre. One of his points, though, sounds pretty damning--apparently historian Melvin Holli once ranked Kucinich the 7th worst mayor in the nation's history:

When [Kucinich] got back into the political fray, his demagogic rhetoric and slash-and-burn political style got him into serious trouble when he stubbornly refused to compromise and led Cleveland into financial default in late 1978 - the first major city to default since the Great Depression. That led also to Kucinich's defeat and exit from executive office.Sounds bad! But if you look at, say, Wikipedia's account of the whole incident, it's not clear that Kucinich did anything wrong. Basically, a private energy firm, the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company (CEI), had been violating federal antitrust law in its attempts to put Muny Light, the city's publicly-owned electric utility, out of business. CEI then engaged in a bit of price gouging to run up the city's light bill.

The previous mayor had planned to pay off the bill by selling Muny Light to CEI. Kucinich was elected mayor after promising to halt the sale. Once he got to office, a bank told Kucinich that it wouldn't renew the city's loans unless he sold off Muny Light. (The bank was later revealed to have a cozy relationship with CEI.) Kucinich refused, and the bank defaulted. Later on, a special election was held on the issue, and Cleveland's voters also refused to sell Muny Light to CEI. Ten years down the road, Cleveland Magazine reported that the refusal to sell had actually saved Cleveland hundreds of millions of dollars in the long run. In any case, Kucinich did exactly what voters wanted, and I don't see how he was the bad actor here.

The previous mayor had planned to pay off the bill by selling Muny Light to CEI. Kucinich was elected mayor after promising to halt the sale. Once he got to office, a bank told Kucinich that it wouldn't renew the city's loans unless he sold off Muny Light. (The bank was later revealed to have a cozy relationship with CEI.) Kucinich refused, and the bank defaulted. Later on, a special election was held on the issue, and Cleveland's voters also refused to sell Muny Light to CEI. Ten years down the road, Cleveland Magazine reported that the refusal to sell had actually saved Cleveland hundreds of millions of dollars in the long run. In any case, Kucinich did exactly what voters wanted, and I don't see how he was the bad actor here.On a more trivial note, Kucinich seems to have lost his 1979 re-election bid in part because his opponent George Voinovich's 9-year-old daughter was killed by a van during the campaign, earning him a tremendous amount of sympathy. (Voinovich already had a narrow lead.) It was a horrible fluke, and Kucinich might've lost anyway, but that doesn't make him a failure. Now sure, by many accounts Kucinich is a terrible person to work for, and his campaign isn't going anywhere, but hey, there's no sense in unfairly smearing the poor guy...

Poverty? Not a Problem

So the reporters at McClatchy snapped on the rubber gloves, plunged into the dark cavities of the Census Bureau, and pulled out a stunning statistic: "Nearly 16 million Americans are living in deep or severe poverty"--a category that includes individuals making less than $5,080 a year, and families of four bringing in less than $9,903 a year. That number, by the way, has been growing rapidly since 2000. The article itself hits the usual refrains--noting that the United States spends less on anti-poverty programs than any other industrialized country outside of Russia and Mexico--but I found this bit near the end quite striking:

The Census Bureau's Survey of Income and Program Participation shows that, in a given month, only 10 percent of severely poor Americans received Temporary Assistance for Needy Families in 2003--the latest year available--and that only 36 percent received food stamps.I doubt those are the only reasons for the low participation rates. As David K. Shipler reported in The Working Poor, welfare agencies spend a great deal of effort dissuading people from applying for assistance. They'll ask single mothers who come in a few perfunctory questions and then--illegally--refuse to give them an application. Or they'll design "Kafkaesque labyrinths of paperwork" that turn any attempt to obtain benefits into a full-time job. Anything to ease pressure on state budgets. Luckily, the Bush administration has taken note of all this and decided to... eliminate the Census's Survey of Income and Program Participation, so that nosy researchers can no longer figure out how many eligible families are receiving assistance. Problem solved!

Many could have exhausted their eligibility for welfare or decided that the new program requirements were too onerous. But the low participation rates are troubling because the worst byproducts of poverty, such as higher crime and violence rates and poor health, nutrition and educational outcomes, are worse for those in deep poverty.

Mean Old Labor Bosses!

Next week, the House will vote on the Employee Free Choice Act, which would allow employees in a workplace to organize as soon as a majority signed cards saying they wanted to do so. (Currently, workers have to go through NLRB-supervised elections that are prone to employer manipulation.) Opponents of card-check argue that labor bosses will just coerce employees into signing the cards, although as Ezra Klein points out, research shows that union intimidation during card-check elections is far, far less common than undue management pressure under the current system.

Anyway, the bill would potentially help organized labor reverse its long decline, but the White House has already promised to veto it, so it doesn't stand much of a chance. That didn't stop Phil Kerpen, though, from taking to the pages of the National Review to attack the legislation:

Under existing law, before a union is recognized, an employer has the right to request a federally supervised secret ballot election. This allows both the union and the employer to make their case and lets workers decide on a union without fear of reprisal.The first bit is rather misleading, no? Employers are very good at manipulating NLRB elections. During the campaign season, managers get to bring workers into captive audience meetings and tell them about all the horrible things that will happen if they unionize. They can make threats and bribes. They get to fire union organizers, and pay a small fine for their troubles. They can delay and delay the outcome until those employees who voted to unionize have long moved on to other jobs. And so on.

Democrats, including congressman George Miller (Calif.), chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee, have historically been strong supporters of the ballot procedure. In 2001 Miller and fifteen other House Democrats wrote to a local government in Mexico: "the secret ballot is absolutely necessary in order to ensure that workers are not intimidated into voting for a union they might not otherwise choose."

Kerpen's other point is disingenuous, and I assume he got it from Heritage talking points on the subject. I can't find George Miller's original letter, but I assume he was responding to the problem of employer-controlled unions in Mexico. According to Human Rights Watch: "Workers must publicly declare their union preference in the presence of numerous employer and non-independent union representatives and even, on occasion, hostile hired thugs." Not surprisingly, Mexican workers usually choose the company union. A secret ballot is an appropriate remedy here. In the United States, by contrast, company unions were outlawed in 1935, and workers have (somewhat) more freedom to choose independent representation. They're two entirely different cases, and Miller's not being hypocritical.

February 13, 2007

Nuclear Diplomacy

The Washington Post has a decent summary of the deal struck between the United States and North Korea:

In a landmark international accord, North Korea promised Tuesday to close down and seal its lone nuclear reactor within 60 days in return for 50,000 tons of fuel oil as a first step in abandoning all nuclear weapons and research programs.The full text is here. John Bolton hates it, but he did make one astute point: "This is the same thing that the State Department was prepared to do six years ago. If we going to cut this deal now, it's amazing we didn't cut it back then." No kidding. It seems likely that North Korea would have accepted this offer before it tested a nuke last year. So why wasn't it done then? Seeing as how North Korea probably won't ever give up what nuclear weapons it now possesses, that looks like a glaring blunder in hindsight.

North Korea also reaffirmed a commitment to disable the reactor in an undefined next phase of denuclearization and to discuss with the United States and other nations its plutonium fuel reserves and other nuclear programs that "would be abandoned" as part of the process. In return for taking those further steps, the accord said, North Korea would receive additional "economic, energy and humanitarian assistance up to the equivalent of 1 million tons of heavy fuel oil."

That said, it's certainly good news that the Yongbyon plutonium facility will be shut down, for a variety of reasons, so credit to the Bush administration. On the other hand, Robert Farley's take seems accurate: "While a success on its own terms, this agreement represents an utter rejection of the Bush administration's approach to North Korea thus far. Carrots, instead of sticks, brought compromises. Nuclear weapons were the subject of diplomacy, not the precondition." Contrast this with the administration's approach to Iran, in which disarmament is the precondition of talks, rather than the hoped-for final goal.

I also wonder how this agreement will fare back in Washington. As Fred Kaplan has pointed out, the Agreed Framework struck by the Clinton administration in 1994 foundered, in part, because Republicans in Congress failed to fund the light-water reactors promised to North Korea. We'll see if Democrats behave differently this time around. Also, Bolton told CNN, "I'm hoping that the president has not been fully briefed on it and he still has time to reject it." So anything's still possible. And, of course, Kim Jong Il could always act erratically and back out all of the sudden...

February 11, 2007

Wind Chill

Over at Slate, Daniel Engber says the whole concept of "wind chill" is utterly meaningless and should be abandoned:

The language of "equivalent temperatures" creates a fundamental misconception about what wind chill really means. It doesn't tell you how cold your skin will get; that's determined by air temperature alone. Wind chill just tells you the rate at which your skin will reach the air temperature.That's certainly interesting, although I do still want something that tells me how quickly I'll get cold, especially if I'm trying to decide how far to walk for lunch. So I say no to abolition. Then again, it's probably easier to poke my head outside and decide for myself rather than stare at the weather forecast and try to make sense of what "wind chill" really entails.

If it were 35 degrees outside with a wind chill of 25, you might think you're in danger of getting frostbite. But your skin can freeze only if the air temperature is below freezing. At a real temperature of 35 degrees, you'll never get frostbite no matter how long you stand outside. And despite a popular misconception, a minus-32 wind chill can't freeze our pipes or car radiators, either.

Lust in Translation

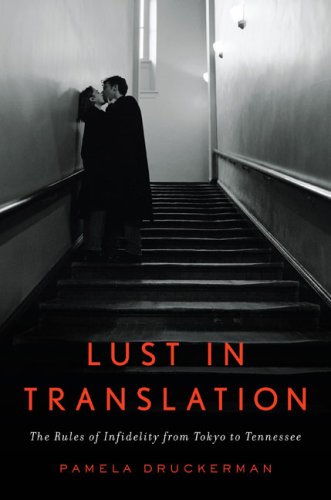

I would've assumed that Pamela Druckerman's new book, Lust in Translation, was great fun to write. But she says that's not wholly true. The book itself looks at how different cultures around the world deal with infidelity—how they view it, how they handle it, how it's accepted. So Druckerman, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, tracked down adulterers in Russia and South Africa, France and Japan, and asked them questions. She got loads of material, and the book is fascinating. But apparently, after months of nonstop chatting with people who were having affairs, it became hard for her not to be suspicious if ever her husband came back an hour late from "soccer practice" or didn't answer his cell phone. It's like the journalistic equivalent of medical students' disease!

I would've assumed that Pamela Druckerman's new book, Lust in Translation, was great fun to write. But she says that's not wholly true. The book itself looks at how different cultures around the world deal with infidelity—how they view it, how they handle it, how it's accepted. So Druckerman, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, tracked down adulterers in Russia and South Africa, France and Japan, and asked them questions. She got loads of material, and the book is fascinating. But apparently, after months of nonstop chatting with people who were having affairs, it became hard for her not to be suspicious if ever her husband came back an hour late from "soccer practice" or didn't answer his cell phone. It's like the journalistic equivalent of medical students' disease!Well, yikes. But like I said, it's a wonderful book. (Among other things, she investigates how the Japanese deal with the fact that one-third of all marriages are sexless.) One thing that stuck out, though, is that it seems that Americans—at least white, middle-class Americans—are the only people who, by and large, see an affair as a symptom of larger problems in a relationship. Bob must've cheated on Sue because they weren't getting along. Or whatever. It can't just be that Bob was attracted to someone else, or was bored and wanted a fling. No. There must be some deeper issue at work.

Russian people, to take just one example, don't seem to view affairs this way—people often have affairs simply because they have tiny apartments and share a bedroom with the kids, so adultery is the only way to have sex. And the fact that Russia has an absurdly high female-to-male ratio—because so many men die young—means that men are in very high demand, which creates additional pressure for infidelity. One 40-year-old women tells Druckerman that "if she didn't go out with married men she'd have almost no one to date."

Anyway, I hadn't realized it, but in the United States, an entire industry has sprouted up to help couples deal with the post-traumatic stress of an affair. And since Americans tend to think that infidelity is a symptom of some deeper problem, there's almost always stress. And, of course, the real problem is never the sex. It's the lying:

Since lying is the problem, truth-telling has become America's cure for infidelity. Many therapists believe that a wife is entitled to ask her husband for the details of every text message and encounter. The rationale is that the relationship between a husband and wife should be transparent. Some couples create a detailed chronology covering the entire period of the infidelity, even if it lasted for several years.Wow. Religious groups have also jumped on this idea that affairs corrupt a relationship, which in turn needs to be "healed." Many Christian organizations are big on truth-telling as therapy, along with religious counseling. (Interestingly, even though adultery is a sin, many Christian groups like the Covenant Keepers see it as a forgivable one, since divorce is so much worse.)

The process stops when the wife can't take it anymore, or when she's satisfied that she's overturned every lie she's ever been told. If any stray lies trickle out after this, the wife can have traumatizing flashbacks. There's no empirical evidence about whether this does any good.

People in some other countries didn't believe me when I told them about America's confession cure. They assumed that knowing the details of what happened would make someone feel worse. But the truth-telling cure has become so widespread in the U.S. that it's now gospel on websites for people with cheating spouses. On the frenetically active SurvivingInfidelity.com, "Erica" says she spent months interrogating her husband about her affair, and then "with the aid of my master calender, the 1000+ email, the photo albums, visa receipts, and his old expense reports, he and I set out to put all of those 2 1/2 years of infidelity on a timeline."

Now, obviously, anecdotal reporting isn't the same thing as doing extensive surveys and the like, but it was interesting that the people in France whom Druckerman interviews were mostly dumbfounded by the notion that couples should never have any secrets between them. That largely seems to be an American idea. (French people also don't appear to think that an affair is always a symptom of some horrific flaw in a relationship.) But then, looking at the statistics, French couples aren't any more prone to infidelity than American couples. It's just dealt with differently.

February 02, 2007

Has Exxon Really Reformed?

I've seen plenty of news reports lately about how ExxonMobil is trying to burnish its public image by becoming more green-friendly. See this story in today's Financial Times, for example. The company has even promised to stop bankrolling the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), which has waged a long disinformation campaign by attacking the science on global warming. This certainly sounds like good news, right?

That's what I thought, too. But today, right as the world's leading climate scientists are preparing to release the latest IPCC report--which will state that global warming has indeed begun and is "very likely" man-made--we get this story in the Guardian:

Scientists and economists have been offered $10,000 each by a lobby group funded by one of the world's largest oil companies to undermine a major climate change report due to be published today.Of course, if there were any scientists out there who had legitimate complaints about the report, they could have worked with the IPCC and registered their objections during the drafting process. But that's not what AEI's going for. This is a smear campaign, intended to sow doubt about the IPCC report in the public mind. Nothing more.

Letters sent by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), an ExxonMobil-funded thinktank with close links to the Bush administration, offered the payments for articles that emphasise the shortcomings of a report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Travel expenses and additional payments were also offered.

So let's see: Exxon has donated $1.6 million to AEI over the years, and there's no indication that it plans to stop anytime soon. And that's not all. Two weeks ago, ExxposeExxon--a coalition of environmental groups, including the NDRC and the Sierra Club--asked Exxon whether it had cut off funds for all of the 43 organizations on its payroll that have attacked climate-change science. Exxon never replied. There's a strong suspicion that the company hasn't really decided to quit spreading confusion about global warming. Instead, it just stopped funding CEI and a few other unnamed groups in order to garner some positive press, and that's it. I believe "greenwashing" is the appropriate term here.

Eyes Off the Ball

Is it paranoid to think that the White House is planning to attack Iran--and soon? Reports like this one, from U.S. News & World Report, keep bubbling up every day:

Democratic insiders tell the Political Bulletin that they suspect Bush will order the bombing of Iranian supply routes, camps, training facilities, and other sites that Administration officials say contribute to American losses in Iraq.Democrats would feel "obliged" to support this? After everything we've seen so far? The Bush administration, meanwhile, hopes to offer up evidence of "Iranian meddling inside Iraq" in the near future--at least once all of those officials who are "concerned that some of the material may be inconclusive" are placated. At this point, I'd prefer that Democrats in Congress quit horsing around with all these "nonbinding" resolutions on Iraq and instead try to prevent the White House from blundering on into Iran. Most of them seem to be in denial, hoping that all these rumors of impending war are just that. But is that really a safe bet at this point?

Under this scenario, Bush would not invade Iran with ground forces or zero in on Iranian nuclear facilities. But under the limited-bombing scenario, Bush could ask for a congressional vote of support, Democratic insiders predict, which many Democrats would feel obliged to endorse or risk looking like they weren't supportive of the troops.